Bacon – Psychological ploys that made bacon go from almost extinct to a breakfast staple and a superb flavor superstar (11 min read)

Bacon’s rise in popularity to a complete food domination wasn’t random. It was the result of Edward Bernays’ habit-forming PR stunts in the 1920s, and the Pork Board’s clever product reframing in the 1990s. They turned bacon into a breakfast icon and a “flavor enhancer” for everything.

tl;dr - Bacon's big break in 30 seconds or less

- 1920s - bacon sales crash as Americans go for “light” breakfasts. Beech-Nut hires Edward Bernays (PR godfather) to save bacon

- Bernays gets 4.5k doctors to say a hearty breakfast (with bacon & eggs) is healthiest

- pre-1980s - bacon is just a breakfast side or in BLTs

- 1980s - health scares hit, demand drops 35-40%

- 1990s - Hardee’s Frisco Burger brings bacon back as a burger “flavor enhancer”

- 2000s - “bacon makes it better” becomes a meme. Fast food, chefs, and internet culture fuel bacon mania

- Today - $4B+ a year in bacon sales, two-thirds of US restaurants serve it, pork belly prices hit record highs, and bacon is now America’s third condiment after salt and pepper.

Bacon craze History Timeline

- Late 1800s - “farm breakfasts” (eggs, bacon, bread, etc) are standard for manual laborers. Bacon is seen as lowbrow by city elites. Mainly eaten in rural homes or seasonally.

- Early 1900s - breakfast gets lighter. Cereal and coffee replace big meals. Bacon is out. Cereal and the idea of “slimness” are in.

- 1924 - Oscar Mayer rolls out pre-sliced, packaged bacon. It makes it easier to buy, but sales are still weak.

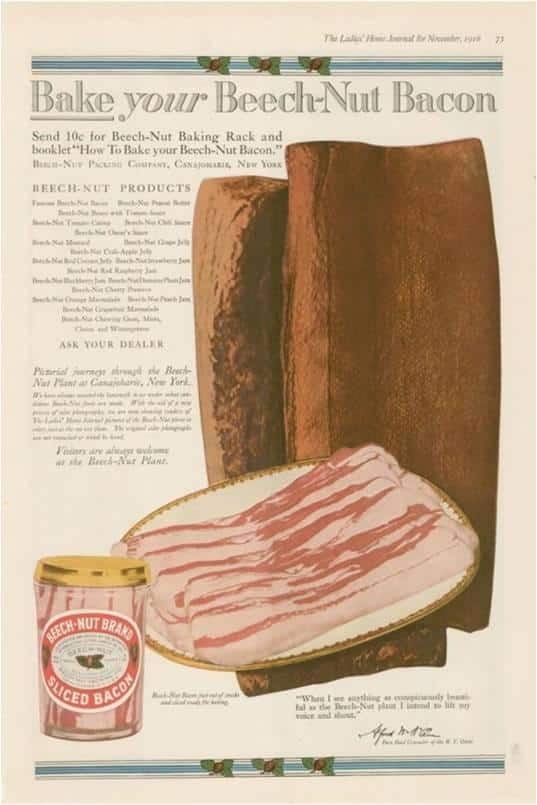

- 1925 - Beech-Nut Packing Co. hires PR legend Edward Bernays to boost bacon demand.

- 1925-1927 - Bernays launches the “bacon & eggs for breakfast” campaign.

- 1927 - US newspapers run “4.5k physicians urge heavy breakfast” headlines, featuring bacon & eggs as the healthy choice. Public buys in. Bacon shows up on breakfast plates everywhere.

- 1928 - bacon sales boom. Beech-Nut can barely keep up.Bernays becomes a legend, writes Propaganda to explain his playbook.

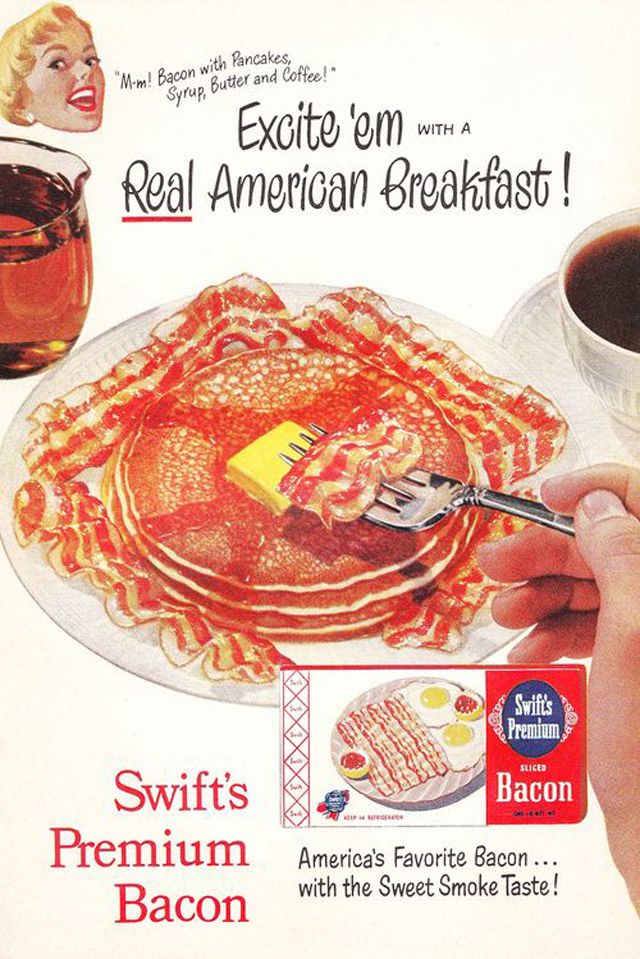

- 1930s - bacon & eggs are locked in as the “all-american breakfast.”

- 1950s-60s - health concerns about fat emerge, but bacon & eggs are too entrenched to vanish.

- 1990s - bacon renaissance. Fast food adds bacon to everything. Atkins and low-carb diets push bacon as “healthy.” Slogans like “Pork. The other white meat” and “bacon makes it better” pop up.

- 2010s - bacon mania hits peak. Bacon festivals, bacon in cocktails, endless memes.

- 2015 - US pork (thanks to bacon) overtakes beef in popularity. 65% of Americans say bacon is basically the national food.

Edward Bernays

The background

In the 1800s, American breakfasts were heavy, with bacon, eggs, even pie, fuel for a day on the farm. But by the early 1900s, white-collar work and new health trends meant lighter breakfasts took over: just coffee, juice, maybe toast. Bacon was out, the cereal craze was in, and most folks only ate bacon with lunch or dinner.

By the 1920s, cereal giants like Kellogg’s (with the “breakfast is the most important meal” line) made grains the morning go-to, while bacon sales crashed. Beech-Nut Packing, a major pork processor, was stuck with mountains of unsold bacon and needed a fix.

Enter Edward Bernays, the PR pioneer (the behind the Torches of Freedom). Beech-Nut hired him to engineer demand. At the time, Americans still liked bacon, but not for breakfast. Bernays spotted an opportunity - if he could convince the public that a protein-heavy breakfast, bacon and eggs, was healthy and satisfying, bacon sales could soar. It wasn’t just a marketing campaign, it was about changing American habits entirely. As Bernays put it, by shaping public opinion, you could “engineer consent.” The bacon-for-breakfast push became a textbook example of manufacturing demand out of thin air.

Edward Bernays' plan

When Edward Bernays took on the bacon account, he knew slapping “Eat Beech-Nut Bacon!” on ads wouldn’t work. The real challenge was changing a habit. Americans didn’t hate bacon, they just weren’t eating heavy breakfasts. So Bernays set out to reframe breakfast itself. Instead of pushing bacon, he sold the idea that a big breakfast is healthy, with bacon at the center.

Bernays and his team, including an in-house doctor, planned the campaign around authority and health. He figured if people thought their light breakfasts were unhealthy, they’d switch to heavier meals. Direct ads from Beech-Nut would look suspicious, so he asked, “Who actually shapes eating habits?” The answer: doctors and nutrition experts. The campaign put doctors in the spotlight, making them the messengers instead of the brand.

Here's his plan:

- Framing the narrative

Bernays built the story that Americans weren’t eating enough at breakfast, which left them with an energy deficit by mid-morning. The fix? A big breakfast with bacon and eggs to “restore energy lost during sleep” and boost health. He framed bacon as medicine, not just indulgence, with the simple logic that your body needs more calories in the morning. - Medical endorsement

Bernays brought in his agency’s doctor (yes, his PR firm had a doctor) to back up the claim. He fed him leading questions until he agreed a hearty breakfast was better. The doctor specifically said bacon and eggs fit the bill. - Consensus creation

The doctor then sent letters to 5k doctors across the country, asking if a heavy breakfast is better for well-being. About 4.5k said yes. It wasn’t a true scientific survey, but it created a convincing stat for headlines. Bernays basically manufactured a medical consensus that big breakfasts (with bacon and eggs) are healthy. - Press release

Bernays turned the doctor responses into a press release: “4,500 Physicians Urge Americans to Eat Heavy Breakfasts to Improve Their Health.” He made sure bacon and eggs were mentioned. It wasn’t presented as advertising – it was “news,” a health finding from the medical community.

Newspapers all over the country picked up the story. Headlines screamed about doctors recommending big breakfasts, and many articles specifically called out bacon and eggs. Because it came from doctors and the news, not Beech-Nut, people trusted it.

Right after Bernays’ campaign hit the headlines, Beech-Nut’s bacon sales shot up. What used to be “leftover” bacon started flying off shelves. Six months after the doctor-backed ads, bacon-and-eggs became the new breakfast standard. Diners, cookbooks, and home kitchens all jumped on the trend, and by the 1930s, “proper” breakfast in America meant bacon and eggs.

Bacon’s dark ages (once again)

For decades after Bernays’ campaign, bacon was a seasonal thing, mostly for breakfast or during BLT season. Joe “Bacon Belly” Leathers said 80% of bacon was sold in stores, with summer tomato crops causing BLT binges, then sales dropped back to normal until next year. This up-and-down demand even led to the pork belly futures market in 1961, with farmers freezing bellies to sell when prices went up.

Then the 1980s hit and America freaked out about fat and nitrates. Leathers remembers bacon sales dropping 35-40%. Suddenly everything was “fat free” - diet sodas, margarine, lean meats. Pork got hammered. The industry pushed “Pork: The Other White Meat” in 1987, trying to make pork look healthy like chicken. It worked for chops and roasts, but not for bacon. Bacon’s fat and nitrates made it the black sheep. Pork bellies piled up, prices crashed to $0.19 a pound, and warehouses overflowed. The US started giving bellies away as cheap exports or food aid.

Bacon became a dirty word in the pork industry. “We just had freezers full of bellies. There was such little demand that the US was literally giving them away,” Leathers said.

From failing to becoming a superior "flavor enhancer"

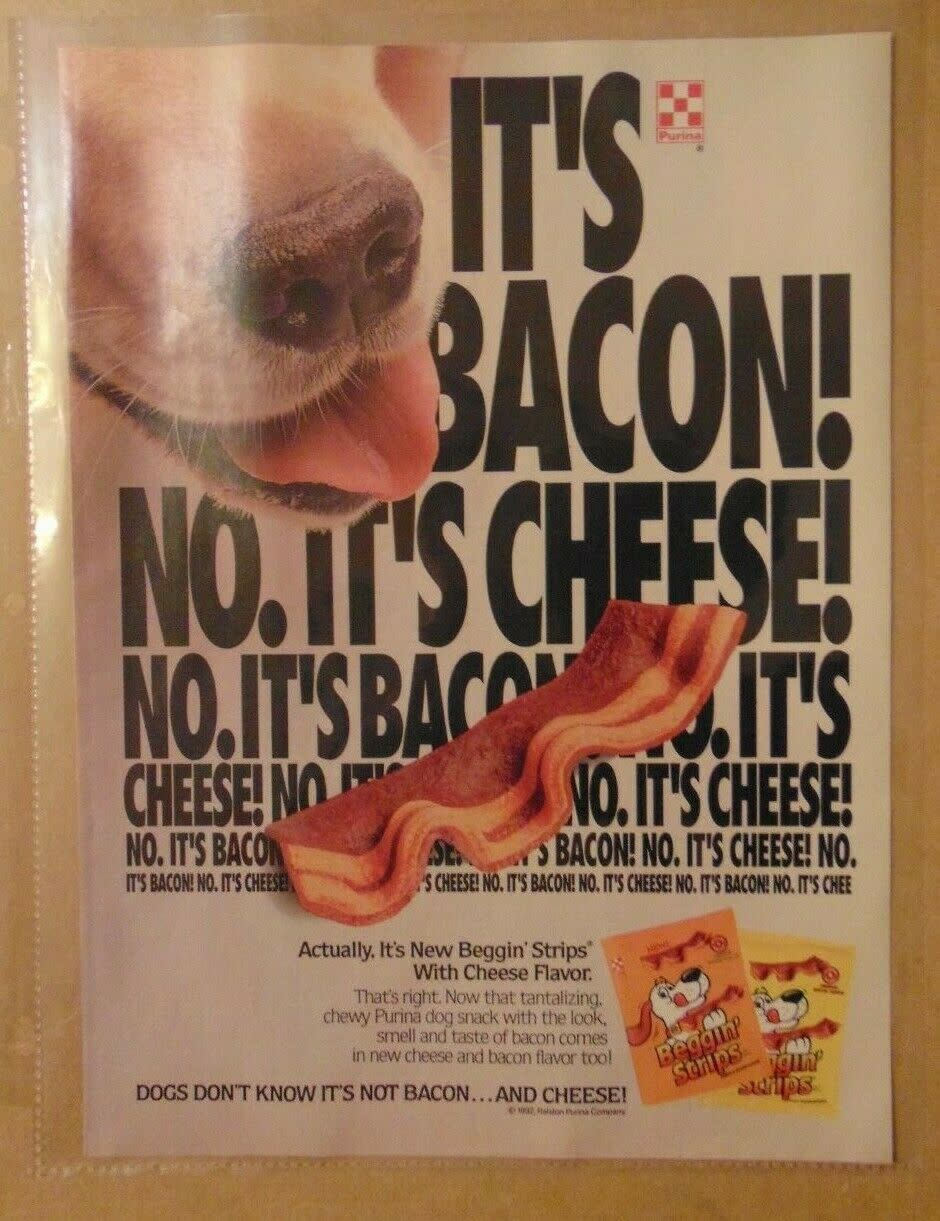

By the late 90s, pork farmers were struggling. Bacon barely sold. Then a few food service marketers pushed a new angle: bacon makes everything taste better. If Americans weren’t eating it for breakfast, maybe they’d want it on burgers, salads, or wraps. They pitched bacon as a “flavor enhancer” and easy upsell.

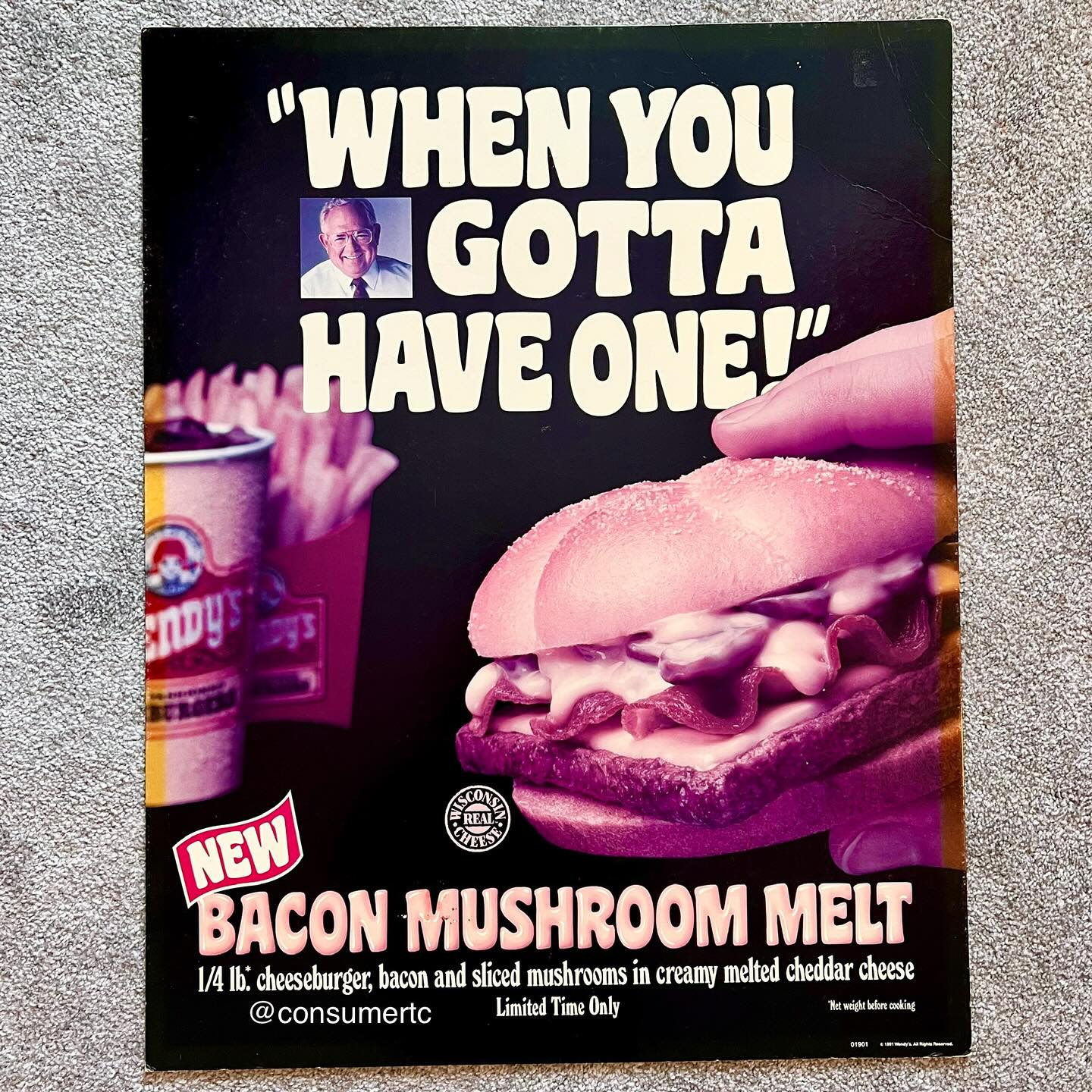

At the time, fast-food chains were pushing lean burgers to follow health trends, but those tasted bland, especially after the 1993 Jack in the Box E. coli scare forced everything well-done. Bacon, with huge flavor for cheap, became a go-to add-on. Hardee’s was first to make bacon the main attraction with the 1992 Frisco Burger - a grease-dripping, bacon-loaded hit. People loved it, health concerns didn't matter. Profit margins were huge, up to 60% for just one bacon slice.

Other chains caught on, but bacon was messy to prep in bulk. The Pork Board and processors poured money into developing precooked, microwaveable bacon and spiral strips that fit burgers perfectly. Suddenly, bacon was easy for every fast food chain to slap onto anything. The Pork Board went all-in, paying for recipe development, lobbying chains to launch bacon-heavy menu items, and running the “bacon makes it better” message everywhere.

It worked. Once Hardee’s, then McDonald’s and Burger King added bacon to more items, every chain joined the party. Burger King dropped the Whopper with bacon, Wendy’s launched the Baconator, and bacon became a staple side. By 2000, bacon was America’s “third condiment,” right behind salt and pepper.

The money followed. Even a small spike in demand made pork belly prices soar from under 30 cents a pound in 1989 to nearly $1 by 2006. Bacon sales shot past $4B. Supermarkets gave bacon entire sections, with endless brands and flavors.

Bacon mania left fast food for fine dining, with chefs like Mario Batali and David Chang making it trendy. Bacon invaded cookies, jams, ice cream, booze, and even lube. Denny’s rolled out the Baconalia menu. Blogs and the internet turned bacon into a meme, with bacon festivals, viral recipes, and merch everywhere. In 2008, people literally named their babies “Bacon.”

Even when “peak bacon” or health scares hit in the 2010s, nothing stopped it. Bacon’s versatility, its status as a burger upgrade, and internet fame kept it growing about 10% a year. It became too big to fail.

Authority Bias

People trust experts, especially when it’s 4.5k doctors all saying the same thing. Bernays didn’t just buy ads, he recruited a medical army. Authority plus bandwagon turns advice into law. That’s why “9 out of 10 experts recommend…” still works today.

Framing/Reframing Effect

Bernays flipped the script. Light breakfast = low energy, and hearty bacon breakfast = healthy, vital, American. Suddenly, skipping bacon was risky, and eating it felt smart, modern, even patriotic. Reframing makes people feel like the behavior they secretly want (big breakfast) is actually virtuous.

Fearmongering and providing solution

The campaign hinted “If you skip a big breakfast, you might be hurting your health.” Fear works, especially when the solution is delicious and easy. This wasn’t terror, just a gentle nudge.

Identity & Belonging

Bernays didn’t just pitch bacon as healthy. He sold it as part of the American identity. The message "Are you a real American? Then you need a proper, hearty American breakfast - bacon and eggs, just like the experts say."

Scarcity & FOMO

In the 1980s-90s, when low-fat trends made bacon a “bad guy,” marketers flipped to scarcity. Now bacon was a treat, a guilty pleasure. Scarcity made people crave it more. Limited-time bacon burgers, “special” menu items, nostalgia and comfort food, all fueled FOMO and made bacon desirable again.

Flavor Enhancer = Reframing ingredient branding

Chains and restaurants stopped treating bacon like just another main ingredient, like chicken or beef, and started seeing it as a universal flavor enhancer, almost like a spice. Suddenly, bacon wasn’t just for breakfast or sandwiches. It became the “secret weapon” you could add to anything. This move turned bacon into an all-purpose upgrade, letting brands add it everywhere and charge a premium for the “bacon effect.”

Meme-ification

Bacon broke out of the food world and became a meme - bacon ice cream, bacon vodka, bacon-wrapped everything. The Internet, TV, and food shows turned bacon into a lifestyle - festivals, merch, inside jokes, even bacon-themed weddings. Marketers just surfed the wave “Bacon makes everything better.”

Window of Opportunity

Window of Opportunity

Bernays’ bacon campaign offers rich lessons for modern marketers, PR professionals, and anyone interested in persuasion:

- Don’t just sell a product, sell a new habit

Bernays didn’t just say “buy bacon.” He reshaped breakfast itself, selling a lifestyle and a cultural norm. The real win is when you change how people see their needs, not just your product. - Use third-party credibility

His secret weapon was third-party endorsements. Today, it’s influencers, experts, testimonials. The lesson: people trust outside voices way more than your own. - Build a strong narrative (emotion + data)

Bernays mixed fear, reassurance, and logic. He made bacon the “solution” to a problem, backed by data and authority. If you want to persuade, hit both the heart and the head, and always frame your product as the hero. - Nail the timing and culture fit

His campaign landed because America in the 1920s craved health, science, and bigger meals. Success often means syncing up with cultural trends, not fighting them. - Respect ethics and public trust

Bernays’ tactics were brilliant but blurred the line between advice and ad. Today, marketers need transparency. Audiences are wise to spin. Don’t abuse authority or fake credibility, or you risk backlash and lost trust. - Play the long game

Instead of chasing a sales spike, he made bacon part of the American morning for generations. Embed your brand in how people live, not just what they buy, and you get loyalty that lasts decades.

Bernays proved that tastes, habits, and “traditions” can be engineered. Marketers can literally rewrite cultural norms if they know how to push the right buttons. But with that power comes the responsibility to stay honest. Bacon at breakfast wasn’t destiny. It was engineered.