5 Cognitive Biases in Pricing to Double Your Conversion This Week (8 min read)

Have you ever wondered why the prices of so many products are somehow similar to one another? There are several marketing psychology techniques in setting prices, based on cognitive biases.

People pay a lot of attention to prices. Various strategies regarding pricing are helpful at increasing sales. Sometimes, a little detail may skyrocket your business. If you want to learn at least some of those popular marketing psychology “tricks”, check out the list below.

1. Charm Pricing

People unconsciously prefer pricing that ends in "9" and "99". This is because such prices “look” as much lower than those ending with zeros.

For example, $299 looks much more like “$200” because our brain acts fast and hooks into the first digit from the whole number. In fact, the price is actually $300, but our brains “reject” the simple calculation of adding $1. This phenomenon has also been proven by Gumroad in their research.

Moreover, the effectiveness of charm pricing stays the same, no matter what's the value of the products. You can observe it in many markets and shopping malls – even the smallest and cheapest products are priced in such a way (e.g. $0,99). According to CBC Radio, in 2014, over 60% of all products were priced like that.

2. Veblen Good

The greater the price of your products, the higher will be the consumers’ demand for them. This is because people like “feeling” rich and having luxurious products at their disposal.

The name comes from Thorstein Veblen, a sociologist who claimed that many of us buy things they don’t even need. He said that people like buying stuff just because it is expensive, and they can afford it.

In practice, if you want to apply the Veblen good effect to your campaign, focus your advertising on your most expensive products. Audi (and many other automotive brands) does it. Most of their low-cost cars don’t even appear on TV or in the Internet ads.

Being in the possession of a Veblen good is often associated with a higher social status. Few of us can afford to drive the newest Ferrari, right? Similarly, Apple winds up the prices of their consecutive models of iPhone.

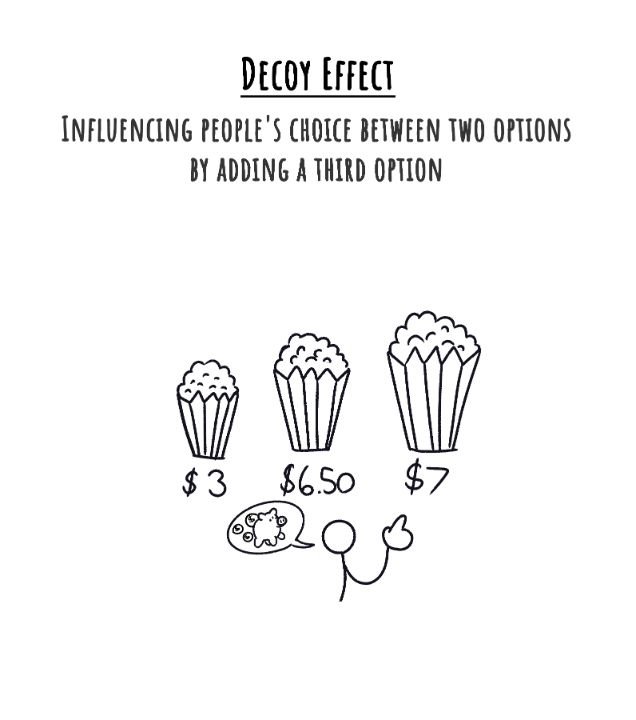

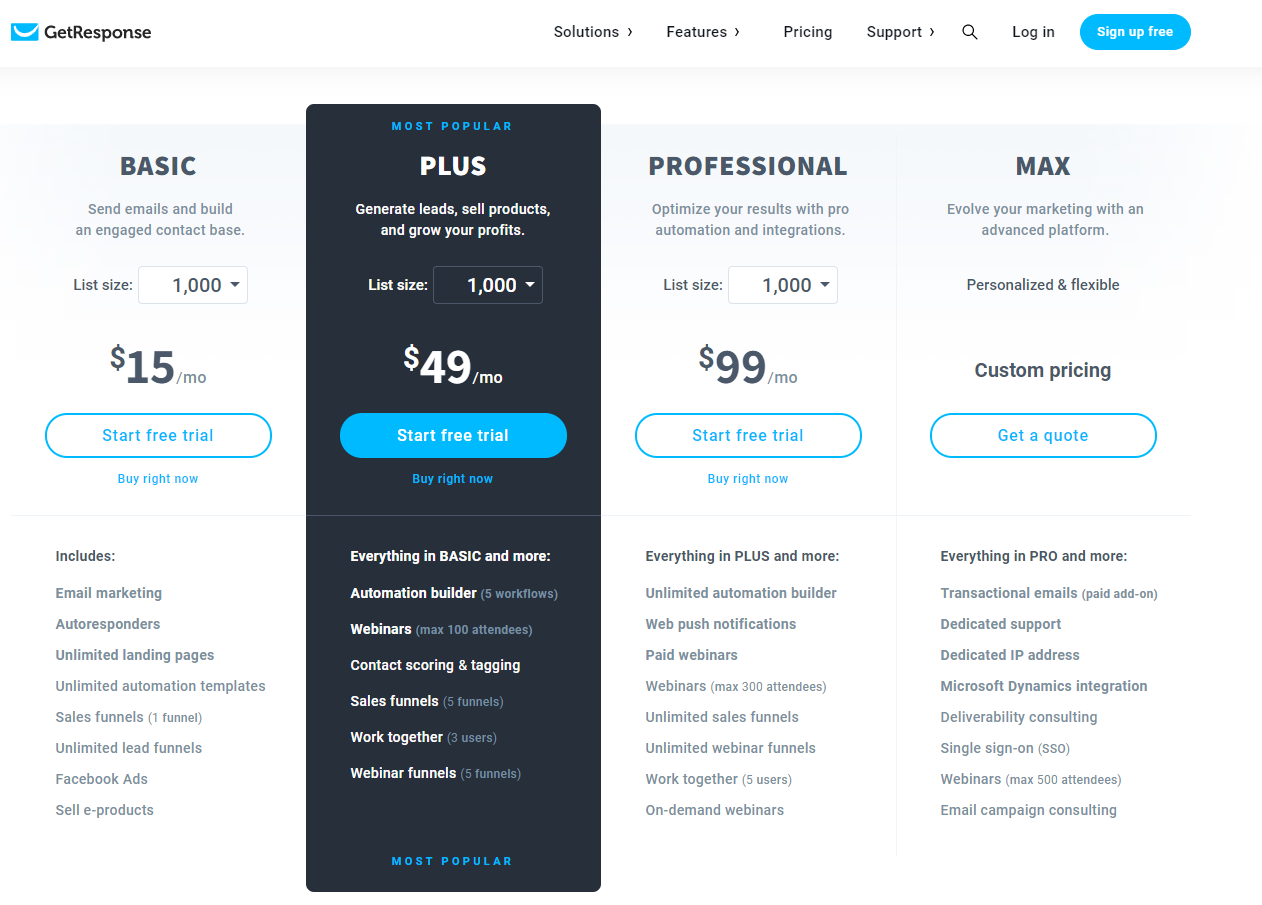

3. Decoy Effect

People change their preference between two options when presented with a third option (the decoy) that is “asymmetrically dominated”

If you offer just 1 price, a customer has 2 choices:

- either to buy or not.

If you offer 2 choices of pricing, a customer has 3 choices:

- To buy the cheaper one,

- To buy the more expensive one,

- or not to buy.

When you add the third pricing option, a much more expensive one, now the situation looks like this for the customer:

- To buy the cheap one,

- To buy the middle one (the previous "expensive one". But now, compared to the third one looks like a bargain)

- To buy the expensive one

- or not to buy.

4. Anchoring Bias

Anchoring bias causes us to rely too heavily on the first piece of information on a topic. Every next option we see is automatically compared by our brain with the first instance we had seen.

People’s minds tend to get stuck on the first value they see. This way, any discount will be much more effective if the original price is crossed out.

For example, to apply the anchoring bias, give the original price of a product/service, and then cross it out. The customers will see how much they gain with that particular discount.

For example:

- “Yesterday: $500. Now: $250”

By the way, mind it that “now” is more dynamic than “today”, too. Giving the new, smaller price right next to the old, bigger one makes it look more attractive.

We interpret each piece of information we get on the basis of (or in reference to) the one we have seen earlier. Research has been conducted to show how people estimated Mahatma Gandhi’s age when being biased by two different values. The guesses were higher as those values were higher, too.

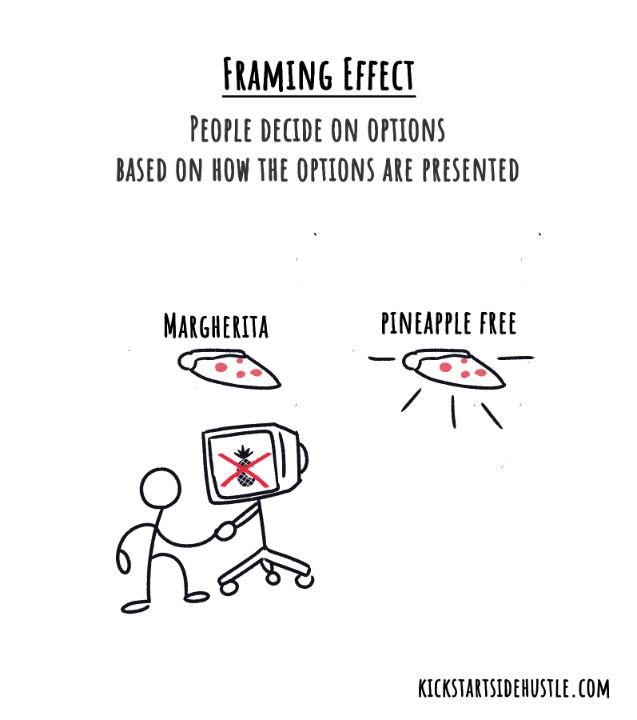

5. Framing

The framing effect is simply about the context in which something is being presented. You can apply it to a great number of situations in order to increase your sale. In this article, however, we want to look at it in terms of pricing.

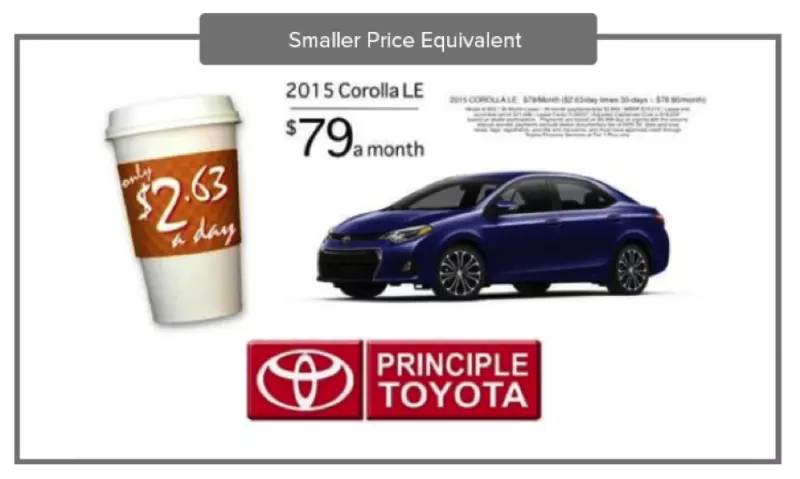

In a way, each of the above marketing psychology strategies could be termed as a variant of the framing effect in practice, too. Yet, in its most basic form, framing in pricing may be used when you’re presenting a subscription plan price. Compare:

- $720 yearly

VS

- $2 a day

Can you see the difference? Which one seems to be more attractive? They mean the same, though, and people won't bother calculating it all the way.

You can also experiment with the fonts and colors of your prices. Try putting big prices in smaller fonts. Try coloring the prices of products for men in red, too. Research has shown that men tend to associate products labelled with red prices as “more masculine”.

It doesn't cost much

It doesn't cost much

Implementing a good pricing strategy doesn't require much effort. Yet, it can bring great results! Our brains function in a schematic way which makes for a perfect conditions to “play with prices”. Try the marketing psychology methods described above and see for yourself.

Get your

"oh sh*t, this might work for us!"

moment in the next 5 minutes

Viral marketing case studies and marketing psychology principles that made hundreds of millions in months or weeks

In the first email:

- a step-by-step strategy that made $0-$30M within 9 weeks with $0 marketing budget (case study)

- cheatsheet (PDF) of 10 biases in marketing used by top 2% companies

Other than that:

- weekly original content that helps you STAND OUT by providing more perceived value with less work

(You won't find it anywhere else)

Explore Cognitive Biases in Marketing